Muons and machine learning provide new window into sealed nuclear storage casks

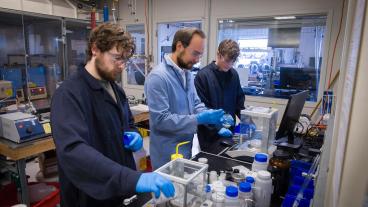

Andrew Osborne, associate professor of mechanical engineering, right, is leading an international team studying how muons and machine learning can produce better images of what’s happening inside nuclear storage casks. Co-PI is Mark Deinert, associate professor of mechanical engineering. (Photo courtesy of DOE)

By Paul Menser, Idaho National Laboratory

At numerous locations throughout the nation, aging dry storage casks contain spent nuclear fuel. Monitoring the radioactivity inside the casks is important for safety, integrity of the casks, and future storage innovations. Andrew Osborne, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Colorado School of Mines, welcomes the urgency of the challenge.

“Our work is focused on assurance that those casks are operating safely,” said Osborne, who earned his doctorate at the University of Glasgow in his native Scotland and is a member of the Nuclear Science and Engineering Program faculty at Mines. With help from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Nuclear Energy University Program (NEUP) and a Consolidated Innovative Nuclear Research (CINR) Phase II Continuation grant, Osborne is leading an international team studying how muons – heavy, high-energy electrons – and machine learning can produce better images of what’s happening inside storage casks.

While the measurement part of the project involved mounting a Los Alamos National Laboratory Giant Muon Tracker around casks for 90 days, the computational aspects, including reverse engineering a data acquisition system and creating new tracking and machine learning codes, may appeal to students not currently thinking about careers in nuclear energy.

“We’re looking for more graduate students and hoping the machine learning is a draw,” Osborne said. There is much to be learned by building new frameworks for examining complex data structures. “We’re hoping to attract top-flight Ph.D. students, even on the data acquisition side,” he said.

High-Energy Muons and Denoising Simulations

Utilizing passive radiation, such as gamma rays from radioactive samples and cosmic ray muons, offers a simplified, less expensive, and safer approach to imaging spent nuclear fuel casks. Unlike traditional methods, the technique does not require external radioactive sources or particle beams, relying instead on detectors.

The inherent limitation, however, is the extended amount of time required for the measurements to be taken, and the signal-to-noise ratios of the images produced. “Using gamma rays from inside, the signal has a lot of noise,” Osborne said.

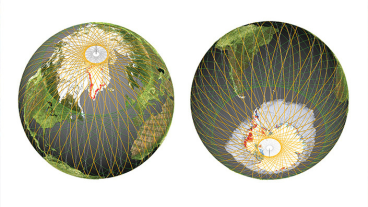

Because of their high energy and mass, muons produced by cosmic rays interacting with the Earth’s atmosphere are well suited for imaging spent nuclear fuel and can penetrate Dry Cask Storage System gamma-ray shielding. They were discovered in the 1930s, when experiments revealed the existence of short-lived, highly energetic particles roughly 200 times heavier than an electron. Their ability to pass through materials, like rock, steel, or concrete, scattering in different ways based on a material’s density, makes them well-suited for monitoring and display in 2D or 3D, revealing the presence of voids, fissures, or corrosion.

The original CINR grant did not include machine learning, but to maximize image quality, the team’s idea was to use simulations of muons to create training data for neural networks models with a view to denoising experimental measurements.

As the project team develops advanced machine learning methods to enhance the resolution and signal-to-noise ratios of passive multimodal tomography images, it is expected that it will improve the sensitivity of dry cask imaging technologies.

This will align with the mission of the DOE Office of Nuclear Energy’s Office of Spent Fuel & High-Level Waste Disposition, to “provide confidence in the safe, long-term management of the nation’s spent nuclear fuel by reducing uncertainty and advancing technology for extended storage.”

Introducing Students to Machine Learning

While there are plenty of open-source software tools and machine learning libraries available, Osborne is keen to have students learn the fundamentals before turning to anything that comes off the shelf.

"We’re ensuring that students and postdocs really understand what they’re doing,” he said. “With a ready-made topology, if it works you don’t really understand why it works. And if it doesn’t, it becomes really difficult knowing where to start."

Osborne said said he encourages students to start simply, with a network consisting of an input layer of neurons, a single layer of hidden neurons, and an output layer of neurons.

“Once I feel a student or postdoc has achieved a certain level of understanding, I will say, ‘Hey, why don’t you try one of the standard ones and see how it compares?’”

NEUP grants have been essential to making this research possible, and he looks forward to similar projects. “Reading [notice of funding opportunity announcements] is a very efficient way of finding out what you are interested in,” he said. “Our graduate level classes are getting larger and larger. These are two technologies with massive potential.”

Administered by NEUP, CINR supports university-led projects related to all aspects of nuclear energy and the fuel cycle. CINR Phase II Continuation funding opportunities, like the one Osborne received, are awarded competitively to researchers and teams that have performed high-quality work through NEUP for DOE’s Office of Nuclear Energy.

Editor's Note: This highlight story from the Nuclear Energy University Program (NEUP) was written by Idaho National Laboratory's Paul Menser and is republished here with permission from NEUP.