Designing possibilities: Addressing the adaptive equipment needs of people with disabilities

Human Centered Design Studio is a two-semester capstone course at Mines focused on developing adaptive equipment for people (and sometimes animals) with disabilities.

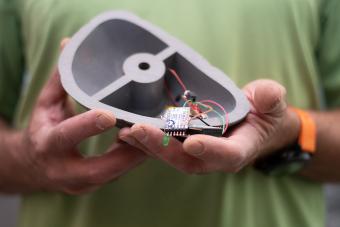

A climbing wall hold that emits sounds for the visually impaired.

Joe DelNero

When thinking of a typical senior design project for a Mines student, chances are, a neoprene bootie for a geriatric hawk is not the first thing that comes to mind. Or next-generation rock climbing wall holds, with sounds for the vision-impaired and programmable LED patterns.

But breaking the mold is the bread and butter of Human Centered Design Studio, a two-semester capstone course at Mines focused on developing adaptive equipment for people (and sometimes animals) with disabilities.

Launched in 2015 by Mechanical Engineering Associate Professor Joel Bach, HCDS operates much like a design firm, with Mines students expected to work on at least three projects over two semesters. The program welcomes new students every semester, which means project knowledge doesn’t disappear when a cohort graduates.

The model works well with the types of projects HCDS takes on. Each requires a different set of skills, and start and end dates often don’t conform to the academic calendar.

“We have projects that take a couple of months. One has been going for three years now,” Bach said. “We can start a project at any time—if it’s an immediate need, we can introduce it to students right away.”

The Human Centered Design Studio worked on 15 projects last year. The following are just a few that were recently completed.

1. Climbing wall holds for the visually impaired

Indoor climbing walls can be a challenge for the visually impaired. Holds are usually in different colors or marked with tape to indicate the difficulty of a particular climbing path.

“Feeling around until they can find the next hold or while someone is barking commands at them isn’t really a great experience for climbers,” Bach said.

In this case, the idea was relatively simple: holds with built-in speakers, set up so only four holds emit sound at any one time—one for each hand and foot. However, at a projected cost of $50 to $60 each, “there’s no way a gym will invest in that,” Bach said.

The solution, a bit counterintuitively, was to pack even more features into the holds. “We put an LED in each hold that can display different colors—you can even start creating different apps and games for it,” Bach said.

“Say you want to climb a 5.11-difficulty route—the wall can remember the holds used and see who did it faster,” Bach explained. “Suddenly, we’ve got something that can appeal to everybody. Not only does it make climbing accessible, it’s hitting the economics of what gyms need.”

Smaller challenges included the presence of chalk dust—anathema to electronic devices—and the noise levels in climbing gyms. These were solved with tighter seals and by allowing the holds’ speakers to be adjusted based on hearing ability.

The last hurdle is powering the holds—having to remove and recharge batteries constantly would be impractical. “We’re looking at wireless charging technology, and if we can do that, we’ll be ready to go commercial,” Bach said.

2. Improved binding for sit ski

Traditional ski bindings, which hold an athlete’s boots to their skis, are designed to release for safety—otherwise, a ski catching on something could easily result in a broken leg.

However, that’s not the case for those who use sit skis, such as Chris Devlin-Young, a Paralympic alpine ski racer who has won scores of medals. “He never wanted his bindings to release,” Bach said, since that would mean a loss of control—equivalent to a car suddenly losing its wheels. And yet sit ski racers have been stuck using the same bindings under their frames, with essentially the entire seat clipped into two potential points of failure.

“In February 2016, Chris crashed at the X Games and broke his collarbone because his bindings failed,” Bach said. “That was a Thursday. The next Tuesday, a team started working on a new binding design, and by May they had a prototype.”

The new design is drastically simplified. Instead of toe and heel plates, a block of aluminum is bolted to the ski. The plate at the bottom of the sit ski then seamlessly slides into the plate and is further secured with a couple of pins.

3. Socks for hawks

Anne Price, chief lecturer with the Raptor Education Foundation, reached out to Bach and his team for help with a geriatric ferruginous hawk in August 2018.

The bird of prey, which came to the foundation in 1996 after her owner could no longer care for her, suffers from a condition that causes ulcers on her talons. This required bandages, but the hawk kept stepping in her water bowls, leading to infections and the bandages coming loose. The hawk also had a habit of removing her bandages, so they needed something secure.

The team started work on the project in mid-October 2018, then tested prototypes the following March. The final product was ready later that month. “The biggest challenge was having an uncooperative client,” Bach said (referring to the hawk, not her handler). The team

worked around this by 3D-printing a model of a hawk’s talon and using that to design a washable, reusable, quick-drying neoprene bootie that her handler could easily take on and off and secure using just one clip.