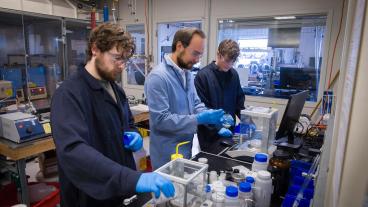

Physics PhD candidate Dakota Keblbeck works in the Subatomic Particle Hideout in Edgar Experimental Mine, where the underground space provides a stable environment for sensitive equipment used in particle physics and quantum computing.

A new kind of laboratory is taking shape in the foothills west of Golden, Colorado. The Colorado Underground Research Institute—known as CURIE—is transforming part of the historic Edgar Experimental Mine, a teaching and laboratory space long used by Mines students and researchers for hands-on mining education, into a one-of-a-kind setting for cutting-edge quantum research.

Shielded by roughly 200 meters of rock, CURIE offers a shallow underground laboratory environment that blocks some of the cosmic radiation that hits Earth’s surface. This helps facilitate low-background physics research, that is, experiments that require ultra-low levels of radiation to detect extremely rare events, such as searching for dark matter or studying nuclear decay. Inside this research hub, scientists are developing next-generation quantum detectors and exploring the properties of neutrinos and dark matter. In spaces like Cryolab 1, systems will operate just a fraction of a degree above absolute zero. These ultracold conditions are key to advancing superconducting and quantum technologies that could power the next wave of quantum computing, communication and sensing.

Together, these efforts place Mines at the forefront of quantum sensing, precision measurement and discovery, bridging physics, engineering, computation and materials science in an environment unlike any other.

We asked Kyle Leach, associate professor of physics and CURIE’s science director, to explain what makes this underground facility a unique asset for Mines and how it’s helping define the future of quantum research.

What research opportunities or challenges was CURIE designed to address, and what makes it a unique asset within Mines’ research ecosystem?

Kyle Leach: CURIE was conceived to tackle one of the hardest frontiers in physics and engineering—measuring, controlling and understanding the faintest signals in nature. By creating a low-background, low-vibration and magnetically quiet underground environment, we’ve opened the door to experiments that simply can’t be done on the surface. What makes CURIE unique at Mines is its connection to the major quantum science initiatives and how it bridges some of our interdisciplinary efforts under one roof—or rather, under a mountain—to push the limits of precision measurement and sensing.

How is the underground environment at Edgar Mine scientifically significant?

Leach: The underground setting at the Edgar Mine provides an extraordinarily stable environment for precision science and future work in quantum computing. Shielded by hundreds of meters of rock, it’s naturally insulated from cosmic radiation, temperature fluctuations and electromagnetic noise. That low-noise environment allows us to uniquely explore various high-profile quantum and subatomic physics studies, including ultra-sensitive quantum systems for fundamental physics, computing and, potentially, national security applications.

What kinds of quantum research projects are underway at CURIE, and what is the impact of this work?

Leach: On campus, we’re currently developing quantum-enabled detectors that can sense energy deposits as small as a single electron volt—energies associated with the kick that a single atom gets following nuclear decay. These technologies are not only reshaping how we study fundamental particles like neutrinos, but also driving innovation in superconducting quantum devices, dark-matter detection and radiation imaging. At Cryolab 1 in CURIE, we plan to explore a range of fundamental and applied science projects that require experimental temperatures that are near absolute-zero. At the moment, the cavern has been excavated, and we are working on preparing the space for the required equipment to achieve this.

How does CURIE’s research scope strengthen Mines’ leadership role within the broader quantum landscape and distinguish Mines among peer institutions?

Leach: CURIE positions Mines as one of the only universities in the world where quantum science is being pursued in an underground research environment. That’s a differentiator—it places us alongside national labs and global centers engaged in cutting-edge quantum sensing and astroparticle physics and makes Mines a unique destination for this emerging class of research. By integrating this capability with Mines’ existing strengths in quantum engineering, materials science, subatomic physics and computation, we’re building a uniquely translational quantum program that connects discovery science directly to engineering and technology.

In what ways does CURIE foster interdisciplinary collaboration across physics, computer science, electrical engineering and more?

Leach: Everything at CURIE is inherently interdisciplinary. Our detectors combine nuclear physics, superconducting electronics, cryogenics and quantum information processing, things we do well across these departments on campus. We have worked with the mining engineers that excavated the space, engineers from companies in the local area on cryostat design and signal readout, with computer scientists on quantum control and data analysis, and with national labs on fabricating devices that reach quantum-limited sensitivity. It’s a true ecosystem—you can’t do this science in silos, and this is really where Mines excels.

Why is this interdisciplinary collaboration important for advancing quantum discovery and technology?

Leach: Quantum discovery doesn’t happen within the boundaries of a single field. Interdisciplinary collaboration ensures that innovation flows both ways—from fundamental physics to applied engineering and back again—and that the next generation of quantum technologies is informed by a deep understanding of nature’s smallest scales. It is here that we have been able to leverage this cross-disciplinary expertise to push the boundaries of what’s possible in quantum science.

What opportunities does CURIE provide for students and early-career researchers, and how do these experiences help prepare the next generation to lead the quantum future?

Leach: CURIE has already given several of our graduate and undergraduate students the training to perform precision measurements in an underground environment through characterization of the small number of cosmic rays that make their way into the caverns. Once we complete Cryolab 1, it will give students the opportunity to work at the edge of discovery in a hands-on way—to operate dilution refrigerators, build superconducting sensors and analyze quantum-scale data in a real underground lab. That experience is rare and transformative. It trains them not only in quantum science but in systems thinking and interdisciplinary collaboration, exactly the skills needed to lead the quantum revolution, whether in academia, national labs or industry.

Learn more about CURIE and the research projects it’s supporting at https://www.curie.mines.edu.

Explore more of how Mines is driving quantum innovation at mines.edu/quantum-research.