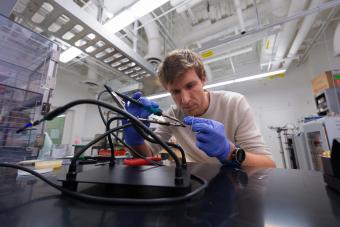

Assistant Professor Wouter Van De Pontseele assembles wiring for cryogenic equipment that will be installed a cryostat to read superconducting sensors.

Story by Jenn Fields, Special to Mines Research

Deep in Colorado’s mountains, a Mines researcher is preparing two unique underground laboratories to answer fundamental questions about the origins of the universe and the future of quantum computing.

Wouter Van De Pontseele, an assistant professor of physics who leads the Quantum Technologies at the Sensitivity Frontier research group, is interested in both particle physics and quantum sensing and computing. His research pursues rare particle interactions that might hold the keys to understanding the origins of the universe. In developing ultra-sensitive instruments for subatomic measurement, his work is at a convergence point where fundamental particle physics and quantum computing meet.

“To perform measurements to test scientific hypotheses and advance quantum computers, we need to build extremely precise detectors to sense things that have never been accessible before,” Van De Pontseele said. “This will let us better understand what limits quantum computing while also probing the mysteries of the universe.”

One of Van De Pontseele’s primary research projects seeks to understand neutrino interactions and mass. Neutrinos are miniscule subatomic particles produced by nuclear reactions in the sun, or the explosion of a star. They travel near the speed of light and have a mass near zero. Trillions pass through your body every second, but because they interact infrequently and weakly with other particles, they’re difficult to detect. But detection could unlock the fundamental physics of how the universe evolved. “They’re important for understanding how big clusters in the universe formed,” Van De Pontseele said.

Muons are also abundant subatomic particles that penetrate Earth’s atmosphere, but in the quest to study neutrinos, the heavier muons can get in the way. “Muons are interesting, but these particles are an annoyance for our experiments,” Van De Pontseele said. “We see the muons, but we can’t see the neutrinos.”

His approach to detection relies on a phenomenon known as superconductivity, where certain materials, when cooled to temperatures near absolute zero, lose all electrical resistance.

“This quantum effect allows us to build detectors with incredible sensitivity,” Van De Pontseele said. “At that scale, even the normal movement of atoms is a source of noise. By getting super cold, we create an environment quiet enough to see things we couldn’t see before, like the tiny energy signature of a single subatomic particle.”

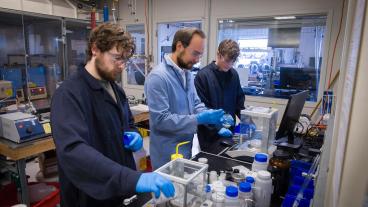

His team is developing cryogenic detectors that use superconducting crystals made from materials like zinc. “My goal is to see how a neutrino's interaction deposits energy in these materials so we can build and scale-up detectors,” he said. This work, he added, could help determine how many types of neutrinos there are and what they weigh, opening a new window in particle physics. Though the research is fundamental, the underlying science has broad potential for real-world applications, such as using quantum computing to simulate chemical interactions for medication discovery or developing quantum encryption for cybersecurity.

Now he’s taking that research underground. Van De Pontseele will be among the first researchers conducting experiments in the two new laboratories slated for the new Colorado Underground Research Institute (CURIE) inside Mines’ Edgar Experimental Mine. This space is proving ideal for the sensitive quantum instrumentation his research team is using—and developing themselves—to listen for the faintest signals.

The first of these lab spaces, dubbed the Subatomic Particle Hangout, is currently equipped with a motorized muon telescope and neutron detectors to characterize the lab, which has about 200 meters of rock overhead shielding it from many of the cosmic rays that constantly bombard Earth and interfere with neutrino detection. Early experiments show the benefits of the lab’s unusual location: instruments have measured 700 times fewer muons than what’s typically measured aboveground. Such ultra-low-background environments are also ideal for quantum computers, which are so sensitive they can be destabilized by minor temperature fluctuations, vibrations or even stray cell phone signals—factors that can be easily controlled or are naturally reduced underground.

Cryolab 1, the second of CURIE’s two lab spaces, will be a clean room and house the ultra-cold refrigerator needed for this work. Van De Pontseele’s team has partnered with Maybell Quantum for the specialized cryostats that achieve these temperatures.

Van De Pontseele hopes CURIE can eventually provide an underground benchmarking facility for Mines’ partners. “Companies could plug in and deploy their novel quantum devices and study to what extent they are affected by noise sources we can control and eliminate at CURIE. This also enables an apples-to-apples comparison between companies and technologies,” he said. “It could help the quantum ecosystem in Colorado and beyond, creating a synergistic quantum test facility.”

He hopes to conduct the first quantum experiments in CURIE in two years. “But the faster the better, because quantum is a fast-moving field.”

Explore more of how Mines is driving quantum innovation at mines.edu/quantum-research.