The lakes deep underneath the Antarctic ice sheet are changing not only in depth but also actively expanding and contracting their shorelines, according to a new analysis of high-resolution satellite data.

The findings, published this month in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, showed that by assuming Antarctic subglacial lakes have fixed boundaries, previous studies underestimated the volume of water moving through the subglacial system by up to 100 percent.

“From a climate perspective, subglacial hydrology could be influential for long term ice sheet stability depending on how water is distributed and evolves below the ice,” said lead author Wilson Sauthoff, a PhD candidate in hydrology at Colorado School of Mines. “Subglacial hydrology is a blind spot in current ice-sheet models. Any new information is useful as it could be a key piece of the puzzle for predicting ice sheet behavior.”

In many places, the Antarctic ice sheet is frozen all the way to the bedrock. But in others, geothermal heat rising from the bedrock, the insulating properties of the thick ice sheet itself and the friction of the ice moving along the bedrock causes the ice sheet to melt from below and form subglacial lakes.

These lakes can form, fill and drain, potentially impacting how the ice above them flows and how much carbon is mobilized from lakebed sediments. But previous studies estimated their location and volume by observing how their filling and draining caused the ice surface to rise and fall over shorter time series with lower resolution data.

“We've never really had data good enough to do this before,” said co-author Matthew Siegfried, associate professor of geophysics at Mines and Sauthoff’s PhD advisor. “It would be like trying to understand how lakes work in the U.S. by just having a single gauge measuring the depth at each lake, but not understanding that some of their shorelines also change.”

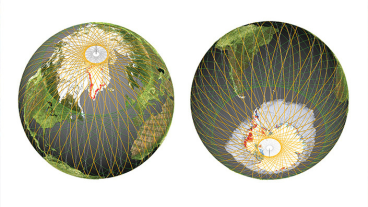

Researchers used high-resolution measurements from two satellites – ESA’s CryoSat-2 and NASA’s ICESat-2 – spanning more than 14 years to track how the boundaries of 158 lakes beneath the ice sheet evolved over time using an anomaly detection algorithm to distinguish lake activity from background ice-surface height changes.

Their analysis showed many of these lakes frequently change shape, sometimes developing expansions or even migrating across the landscape.

“Subglacial topography is complex and varied,” Sauthoff said. “As these lakes go through fill-drain cycles, their boundaries or ‘footprints’ change shape or location, which we found has a huge impact on how much water is moving through the subglacial environment.”

The researchers also used the data about the changing boundaries of subglacial lakes to generate a time series of estimated dissolved inorganic carbon production from the lakebeds. Led by co-author Ryan Venturelli, assistant professor of geology and geological engineering at Mines, their estimates indicate large overestimates of carbon production when using stationary lake boundaries. Also co-authoring the paper was Benjamin Smith, principal physicist at the Polar Science Center at the University of Washington.

Read the full paper, “Dynamic Boundaries of Antarctic Active Subglacial Lakes Reveal Underestimated Water Fluxes and Overestimated Lakebed Active Areas,” on the Geophysical Research Letters website. The research was funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation.