Jesse Rocha of Alliance Technical Group prepares to conduct air emission monitoring on several PFAS destruction technologies being tested side by side at Peterson Space Force Base during the summer of 2025. The Colorado School of Mines-led project was the first “apples to apples” assessment of destruction technologies conducted on PFAS-impacted sediment and researchers also gathered data on each technology's air emissions. (Photo by Tim Meyer/Colorado School of Mines)

New technologies that tout their ability to destroy per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) need to be evaluated not only for their effectiveness and efficiency but also for the byproducts they might release into the air.

That’s the message from an international group of PFAS experts hailing from academia, government and industry published today in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment.

The airborne byproducts of PFAS destruction technologies – known as products of incomplete destruction (PIDs) – have the potential to be just as problematic as the so-called “forever chemicals” from which they are derived, said senior author Christopher Higgins, AMAX Distinguished Chair in Civil and Environmental Engineering at Colorado School of Mines.

“We're about to embark on billions of dollars in cleanup of PFAS-contaminated sites, where the goal isn't just removing the contaminants from the water or soil but destroying them," Higgins said. "If we aren't putting adequate controls on what we're potentially emitting into the air, we may cause additional problems for those communities handling the waste or our local communities if destruction is done in a distributed manner.”

“From a technical perspective, PFAS-derived PIDs for all intents and purposes are still PFASs – they have the potential to be very, very persistent and just as problematic,” he said.

A large class of synthetic organic chemicals, PFASs have been widely used in industrial processes and consumer products since the 1940s – in everything from waterproof textiles and nonstick cookware to the firefighting foams used at airports and military installations. But the chemical and thermal stability that makes them useful in so many applications is also what enables them to persist in the environment for as long as they do.

In the paper, Higgins and coauthors from Mines, North Carolina State University, University of Notre Dame, Virginia Tech, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Navy, Alcoa, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (Germany), York University (Canada) and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (Australia) review the PIDs released by both existing and emerging PFAS destruction methods and approaches to categorize and measure them.

Current technologies use a variety of approaches to degrade PFASs, with varying degrees of success. Many achieve destruction and removal efficiencies of more than 99.99 percent – but that metric does not account for the formation of airborne PIDs, researchers say.

“Numerous existing and emerging technologies can effectively eliminate commonly measured PFASs. What is less well known is what compounds are produced in the process," said co-senior author Detlef Knappe, S. James Ellen Distinguished Professor of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering at NC State University. "By applying new analytical methods described in this paper, researchers are making significant progress in understanding PID formation and emissions from destruction methods. These efforts are enabling decision makers to select technologies that can safely destroy PFASs."

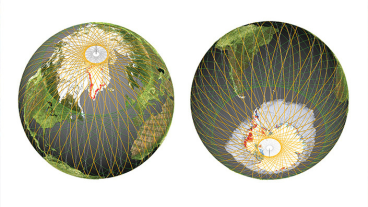

The authors suggest the use of a broad set of analytical methods to comprehensively characterize PIDs and thereby minimize airborne emissions. Otherwise, airborne PIDs can be transported over long distances in the atmosphere, broadening the potential for environmental impact and the risk of human exposure through inhalation or ingestion of contaminated air, water and food.

“The issue with an incomplete understanding of PFAS and PID emissions is that once they have inadvertently escaped into the atmosphere, they are nearly impossible to retrieve,” said co-author Jens Blotevogel, Principal Research Scientist at Australia's CSIRO. “Fortunately, our rapidly emerging understanding of destructive PFAS treatment is giving us the confidence that - if done right - it can be achieved in a safe and effective way.”

Read the full paper, “Air emissions during destruction of PFAS-containing materials,” on the Nature Reviews Earth & Environment website.