Under a watchful eye: Using nighttime lights to inform science and public policy

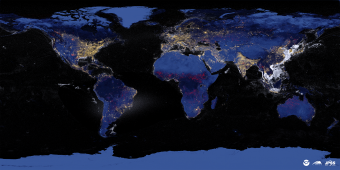

A VIIRS world map of nighttime lights.

Some of the most iconic images of humanity’s presence on Earth come from above the clouds—high-resolution images of nighttime lights taken by the satellites in orbit just beyond our atmosphere. But these images aren’t just for show. Rather they—and other nocturnal radiant emissions—are being used for scientific and public policy applications by the Earth Observation Group that recently joined Mines’ Payne Institute for Public Policy.

The EOG is dedicated to the development of data products that use satellite imaging to provide valuable insights on gas flaring and volcanic activity, poaching, power outages and electrification, geomagnetism and more.

We asked Christopher Elvidge, director of the EOG, about the applications of this research and how this data can help us better understand the scope of humanity’s effect on the Earth.

Q: What can nighttime observations tell us?

Elvidge: Daytime satellite data are great for monitoring crops, vegetation, ocean color, snow and ice. At night, it’s possible to detect human activities, such as power consumption, the outlines of human development, vessels carrying lights and gas flaring.

Q: How are nocturnal radiant emissions being used for public policy applications?

Elvidge: The data from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program and Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite are available on an open-access basis and span 1992-2019 and form one of the longest continuous series of global satellite data products. The data are used

to map urban and peri-urban boundaries, population, economic activity, spatial distribution of fossil fuel greenhouse gas emission, density of constructed surfaces, astronomical light pollution, power outages, rural electrification and nocturnal lighting impacts on organisms, such as sea turtles.

Each year, there are more than 10,000 natural gas flares identified with VIIRS data, which are individually cataloged with locations and estimates of flared gas volumes, and the data are used by the World Bank and many university researchers.

In 2015, EOG began work on an algorithm to detect boats with their lights on. This led to a new nightly global product, called VIIRS boat detections, used by navies, coast guards, fishery agencies, researchers and environmental organizations. EOG sends email and text alerts for detections for more than 1,000 protected waters and fishery closures in the Philippines, Thailand and Indonesia. In the Philippines, the alerts are used to plan and conduct enforcement actions for illegal commercial fishing operations in restricted coastal waters.

Q: What are the challenges of this research?

Elvidge: We are always limited by the capabilities of the sensors we have access to. The VIIRS collects data only once or twice per night, and these are after midnight. Perhaps in the future, we will have low-light imaging data collected at multiple time during the night, with higher spatial resolution and more spectral bands.

For more information about the Earth Observation Group and Mines’ Payne Institute for Public Policy, visit payneinstitute.mines.edu.