Mines is preparing students to become well-rounded leaders, innovators through blend of technical rigor, creative learning

By Sarah Kuta, Special to Mines Magazine

On a sunny afternoon last fall, a group of Mines undergraduates gathered on the lawn outside Alderson Hall for their robotics class. They stood in a circle, clapping their hands and gesturing at each other while calling out, “Zip! Zap! Zop!”

Once they’d warmed up, they moved on to other improvisational theater exercises—like pretending to assemble an imaginary table and move it across the grass.

But what does improv theater have to do with robotics? Everything, if you ask Tom Williams, associate professor of computer science and director of the Mines Interactive Robotics Research Lab. That day on the lawn, Williams was demonstrating how useful theater-based role-play exercises could be for programming robots—more specifically, social robots that need to have realistic, human-like gestures. He was using improv to help his students become better robot designers.

“The skills necessary for successful improvisation are the same skills needed for social robots,” he said.

The mash-up of improv theater and robotics is just one example of the many unique ways Mines is integrating the humanities into its science and engineering curriculum.

The university may be renowned for its technical rigor and expertise in applied science and engineering. But Mines is also enhancing students’ education by seamlessly blending the humanities, arts, social sciences and other related fields into its curriculum—often, in surprising and creative ways.

The university’s multidisciplinary approach—which goes far beyond Nature and Human Values—ensures students graduate not only as technical experts, but also as effective communicators, well-rounded professionals and good global citizens.

Through a variety of humanities-focused experiences and courses, Mines students learn to successfully navigate the human and community aspects of technology and innovation. They practice collaborating across disciplines, making ethical decisions and connecting their work to society—all while keeping different key stakeholders in mind.

And, by the time they graduate, Mines students have mastered storytelling techniques that help them effectively explain their research, engage with the public and articulate their ideas to diverse audiences.

“Having technical knowledge is extremely important,” said Jerry Grandey ’68, who started the Grandey Leadership by Design First-Year Honors Experience at Mines to help students learn leadership principles that they can carry throughout their professional lives. “But you’re at a disadvantage if you can’t communicate. Whether you’re just solely technical or migrating into more of a supervisory or managerial position, ultimately, you need to be able to communicate effectively.”

Designing human-like robots

Many of these experiences are offered through Mines’ Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (HASS) Department. But they’re also sprinkled throughout the university’s science and engineering classes—like Williams’ Human-Robot Interaction course.

Offered through Mines’ Computer Science Department, the class focuses on social robots—such as those used in some hospitals, airports and schools. For these robots to be useful and effective, they must be able to interact with humans through verbal and nonverbal communication. This means the professionals designing and programming them need to think critically about how they should look, sound and move.

“If you want the interactions to be fast, seamless, comfortable and natural to people, then you need to account for the types of interactions that humans find to be comfortable and natural,” said Williams. “You don’t want to have to train people how to use a robot. People need to be able to rely on what they know about human-to-human interactions to interact with social robots.”

Often, before they start programming, designers will act out specific scenarios or behaviors they think might be useful for their robot. Several years ago, Williams realized the skills new performers learn in improv theater—something he does as an art form in his free time—are the same skills we’re trying to give robots. The skills as they’re thought about in improv theory can serve as a blueprint for social robot design requirements, and the ways those skills are taught to improvisers can serve as a blueprint for social robotics design education.

“I started thinking, maybe what we are doing in social robotics is really the same thing—it’s just, instead of training an actor to carefully observe their improv partners and formulate an appropriate response using natural body language and gaze and gestures, we’re doing it with robots that are otherwise not very sociable,” he said.

In Fall 2024, Williams brought in members of a Denver-based improv troupe—named, fittingly, Not My Robot—to lead his students through various improv games and exercises. Toward the end of the session, students also acted out storyboards they’d sketched depicting envisioned interactions between their robots and humans. With feedback from fellow students, they revised their storyboards, which they later used to program their robots.

“Mines is so focused on building real technologies,” said Williams. “If we want to be able to develop technologies that are actually used by real people and that are out in the real world, then it’s really important for students to understand the human side of the equation. How do we know these technologies are actually helping people? What are the opportunities to meaningfully enhance human capabilities and human flourishing?”

Inventing new musical instruments

Mines’ humanities curriculum is also giving students a chance to use their hard-earned technical expertise in novel and fun ways. In many cases, these interdisciplinary projects and classes end up being some of the most memorable experiences students have during their time at Mines.

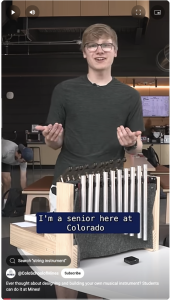

That’s how current Mines student Jonah Booth feels about the “Xylofraud,” a quirky musical instrument he helped invent during his Reevaluation of Design and Sustainable Future of Musical Instrument class last fall.

Taught by Masakazu Ito, director of the Mines Philharmonic Orchestra, the course encourages students to think critically about how musical instruments have been designed and built historically—and how they might improve upon those designs or come up with new tune-producing gadgets altogether.

The students spent the semester coming up with the idea, designing the instrument, fabricating the components and putting them all together. (No easy feat because, including screws, the Xylofraud has roughly 400 parts, according to Booth.) Then, they made a humorous video to explain their invention that has racked up more than 26,000 views and counting on YouTube.

The Xylofraud likely won’t become mainstream. But, while building it, Booth said he learned many valuable lessons that will help him in his mechanical engineering career. Most notably, the project encouraged him to go big, take risks and embrace his creativity, even if that resulted in an imperfect outcome.

“We didn’t have to dial the project back to follow specific guidelines or meet rubric requirements—we could just go for it,” he said. “Even failure was celebrated in that class—we didn’t necessarily have to make something that works, as long as we tried.”

Because of the freedom and flexibility the course gave them, Booth said his group decided to tackle a much more complicated, challenging project than they might have otherwise. That “boundless creativity” helped Booth stretch his engineering skills, he said.

In addition, he enjoyed working with students from outside his major. Everyone brought their own unique perspectives to the project, which ultimately made it stronger.

“The communication and teamwork skills you get from that are really valuable,” said Booth.

In the end, the group produced something they were all extremely proud of—a brand-new, never-before-seen musical instrument.

Exploring water rights through performance

Other humanities courses help students think about long-standing problems in new ways—like water rights in the moisture-starved U.S. West.

Water rights can be confusing and boring to the average person. But they’re vitally important for both policymakers and members of the public to understand. Shannon Mancus, an associate teaching professor and HASS associate department head, wondered if Mines students could help bring this often-overlooked topic to life by writing and producing a play.

Working with Adjunct Professor Joseph Bearss, she developed a project-based Science on Stage course to explore how theater and performance can communicate intricate scientific and technical problems successfully.

“Our students are so creative, they’re incredibly good problem-solvers and they’re excellent communicators as well,” she said. “I had a sense that they would be able to pick up the idea and run with it—and boy was I right.”

During the Spring 2025 semester, students learned about character development, studied the mechanics of immersive theater and investigated storytelling as an effective method for communicating environmental ideas. Using what they learned, they also put together a detailed creative guide that might someday serve as the blueprint for an immersive theater production about water rights.

With these and other HASS courses, Mancus hopes to encourage students to think outside the technical box. Nearly every scientific problem also has some sort of social or cultural component—and engineers must take those into account to be effective.

“Students understand that what they do doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” she said. “It happens in society and culture and it’s important to understand how those things operate.”

The humanities can also help students develop the soft skills they’ll need to excel in their careers. Today’s engineers must be technically competent, but they must also be emotionally intelligent, adaptable, collaborative, creative and thoughtful.

“Your engineering classes are going to get you a really great job,” said Mancus. “The skills you learn in your humanities classes can help you get promotions.”