‘Every American has PFAS in their blood’: Mines professor researching how ‘forever chemicals’ interact with other materials in the environment

The U.S. government recently announced a multi-agency effort to address per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in the environment. The plan includes a strategy to prevent PFAS from being released in the air, drinking systems and food supply, as well as actions to expand cleanup efforts for PFAS already polluting the environment.

PFAS, sometimes called “forever chemicals”, are man-made chemicals that are widely used and break down extremely slowly over time. Their use is so widespread that they can be found in the blood of people and animals all over the world, and are present at low levels in a variety of food products and in the environment, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

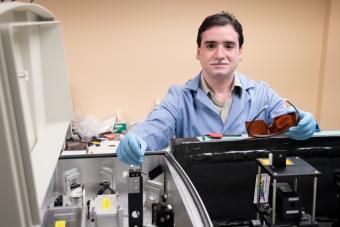

At Colorado School of Mines, researchers are addressing the PFAS problem from different angles. Shubham Vyas, associate professor of chemistry at Colorado School of Mines, has received a $455,655 grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to study the reactivity of PFAS within the environment. This is the third NSF-funded grant Vyas has received in the last four years related to PFAS research.

“PFAS are a very complex set of chemicals,” Vyas said. “Most of what is usually studied is what we call legacy PFAS. But there are many more that exist that are not regulated by the EPA. And we need to understand what happens to all of them when they come into the environment.”

Vyas and his students will focus on chemical reactions of PFAS with various reactive species, such as carbonate radicals, and the role metal ions play in this process. The grant funds PFAS research by Vyas and his students for three years.

Vyas stressed how crucial learning about PFAS is because the scientific research on them is relatively new. But they’ve been known to be toxic and ubiquitous for much longer, and science is trying to keep up with understanding their widespread use and what it means for the environment, he said.

“Nearly every American has PFAS in their blood, and they get passed on to the next generation presumably through breast milk,” Vyas said. “The scientific research community have only begun to truly realize their biologic, toxic effects for 10 to 15 years. But now that we know, what are we going to do about it?”

Vyas has been working on the topic of PFAS since 2014. He focuses on the science behind PFAS and how to better understand them, so engineers can make more efficient systems to filter them out of the environment.

“Most solutions right now use existing technology that works for other chemicals, and then figuring out if they work for PFAS,” he said. “But they’re not the best solution for PFAS and that’s what piqued my interest. As a scientist, how do I look at fundamental reactions? How do we make newer technologies that work specifically for PFAS?”

Vyas said the best way to approach the problem of PFAS is for engineering and science to work together. Engineering solutions focus on separating PFAS from water and then breaking them apart, and science can help improve those processes with research, like the research Vyas has been conducting for seven years now.

“I collaborate with engineers, but I work more on the science part,” he said. “Whatever data they have, what does it mean? If an engineering process works, and the efficiency is at 10 percent, how do we improve that? Let’s get back to the science, and see how sunlight, temperature, everything in the environment, is affecting the process.”

Vyas said another important aspect of this NSF grant is that students will get firsthand training, which will serve them going forward, after they finish their studies at Mines.

“Through this grant, we’re training the next generation of scientists,” he said. “They’re building on what we’ve learned about PFAS through previous grants and using those computational methods and instrumentation, and carrying it over, which only makes it better.”