Colorado School of Mines researcher helps validate new approach for PFAS blood testing

A Colorado School of Mines professor is part of a team of researchers that has demonstrated that PFAS exposure testing can be effectively conducted with the prick of a finger, in addition to the more traditional blood draws.

PFASs, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of more than 9,000 chemicals that are used widely in industrial and consumer products. They are commonly known as “forever chemicals” due to their extreme persistence in the environment and the human body, where they can remain for many years. PFAS cross the placental barrier and accumulate in the growing fetus, have been linked with a wide range of health effects including high cholesterol, several cancers, infertility and low birth weight. They have contaminated the drinking water for millions of Americans, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently proposed a drinking water goal of zero for two of the most common PFAS, PFOA and PFOS.

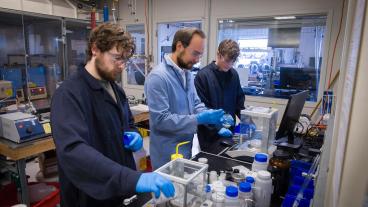

Chris Higgins, University Distinguished Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Mines, was one of the co-authors on the new study, published today in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Science & Technology. The authors, hailing from Michigan State University, Duke, Eurofins Environment Testing and Mines, examined PFAS exposure measured by self-collection of blood – via a new finger prick technique – and traditional blood draws.

A total of 53 people with prior PFAS drinking water contamination provided a blood sample collected by a blood draw and then pricked their finger using a lancet and used the new sampler to collect a precise volume of blood. The blood samples were analyzed by Eurofins for 45 PFAS, five of which were detected frequently enough in the samples for the comparison.

The results showed similar detection frequencies and high correlations between the two approaches. Lead author on the study was Courtney Carignan, assistant professor at Michigan State.

"This is a critical effort, as it provides us with confidence that self-collected blood samples provide just as good – if not, in some cases, better – data on human exposure,” Higgins said. “Just as importantly, though, these are much easier to collect than traditional serum samples, and thus this really opens the door for bigger-scale PFAS exposure assessment efforts.”

In addition to being more accessible, the self-collected whole-blood samples may even offer a more comprehensive picture of the PFAS in our blood, including compounds such as FOSA, Higgins said. FOSA (perfluorooctane sulfonamide) is a PFAS that was detected in approximately half of the whole blood samples, but not in any of the serum samples.

While the authors concluded the new approach is promising, they cautioned that users should take care to ensure proper self-collection and use sufficiently sensitive analytical methods. Also, the appropriate conversion must be applied when comparing with levels in serum, which some labs like Eurofins will do but others may not. The authors reported that simply multiplying the whole blood concentration by two provides a good estimate of the serum equivalent.

“People with drinking water contamination often want to know their PFAS blood levels, but have trouble gaining access to a blood draw and quality testing,” Carignan said. “Blood test results can be used to document exposure, compare with levels in the general populations, inform exposure reduction and to take health protective action.”

Study authors included Carignan and Rachel Bauer at Michigan State University; Andrew Patterson, Thep Phomsopha, and Eric Redman at Eurofins Environment Testing; Heather Stapleton at Duke University; and Higgins at Colorado School of Mines.

“The ability to use a finger-prick device to measure PFAS exposure opens up new research opportunities, and importantly, allows people in the general public to test their own blood without having to be part of an academic research study,” Stapleton said.

To read the full study, “A self-collection blood test for PFASs: Comparing volumetric micro-samplers with a traditional serum approach,” go to https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.2c09852.